Our speedboat, the Jolly Breeze, rocked a little with the comings and goings of the Bay of Fundy waves. Nearby was a small island adorned with a red and white lighthouse, its rocky shores blanketed with cormorants, gulls and shearwaters squawking away the remainder of morning light. My camera was trained on the water.

After perhaps a minute’s wait, it turned from a shimmering blue to seething white. The few of us in the boat who understood this harbinger pointed and howled for our attention, just in time to catch the spectacle. Together, a pair of humpback whales broke the water, heads first. Just as their dark blue forms cleared the waves, their mighty mouths slammed shut and they fell away from one another, their enormous bodies crashing downward with perfect synchronicity. It happened so quickly that my pictures were a blur, but I didn’t care. After this spectacle, my mood was immutable.

Such was my morning on the Bay of Fundy, followed shortly by a curious pod of harbour porpoises and still more seabirds, a beautiful northern gannet hovering overhead so as to scrutinize these enthusiastic primates. Nearby, minke whales spouted, Fin whales remained elusive on the horizon and on the rare occasion, a humpback would throw itself entirely out of the water, coming down with tremendous force and throwing up a curtain of mist. This is called a breach.

After visiting my humpbacks, courtesy of Tall Ship Whale Adventures, I travelled to the Isle of Grand Manan. The Bay of Fundy belongs to such creatures, and of course, the people who study them, working from a repurposed house immediately in front of my arriving ferry.

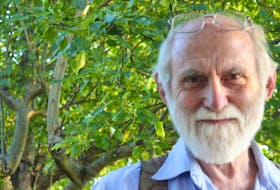

This group of researchers was founded in 1981 by the late Dr. David Gaskin for his pioneering research of the several marine species occupying the Bay of Fundy. In particular, he studied the harbour porpoise, even doing basic anatomy for the scientific literature. Today, their aforementioned house is called the Grand Manan Whale And Seabird Research Station, carried on, among others, by executive director Laurie Murison.

The station, a registered Canadian charity, tries to cover the costs of travel, food and accommodations for its visiting researchers and grad students but otherwise, their work is entirely volunteer. Murison explained to me that their subjects of study are more varied than elsewhere, at the mercy of whomever makes up their core staff.

At present, some of her colleagues are studying fats across the spectrum of the Bay of Fundy marine life, and making important discoveries about the dietary and digestive aspects of whales. Another researcher is focusing instead on the basking shark, the second largest species on Earth about which very little is known. By way of satellite tags, these giants are being tracked so more can be learned about their preferred habitat. These same tags are also collecting climatic data from the waters these sharks visit, bolstering our understanding of regional climate change. Still more research concerns the toxicology of these animals, and which of our pollutants they happen to be suffering from. The more we understand these species and their realm, the better equipped we will be to protect them.

Their work on lobster, for example, suggests that this species’ most fertile members are not in fact the exceedingly large ones of advanced age, as has been widely assumed for some time. Instead, the midrange lobsters, the ones we target readily in our fisheries, might be most responsible for replenishing lobster populations year after year. It’s a startling possibility in need of continued attention.

Murison herself keeps a close eye on the right whales which, until recently, showed the Bay of Fundy a great deal of annual patronage. Now that they’ve begun spending their summers in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, she lends her expertise to education about the dangers of active and abandoned traps entangling right whales, about the careful placement of such traps to avoid them and about the alternative trap technologies being taken ever more seriously.

She makes particular note of “acoustic release,” where a trap’s rope is coiled up harmlessly underwater until unravelled by an acoustic pulse for later collection. In this way, fewer ropes await our right whales, and fewer traps are lost as a result. Much of their research is dedicated to conservation in this fashion.

A great deal of important work is being conducted at this station, and in the Fundy waters surrounding its island of choice. What amazes me is the shoestring on which their research is dependent, and how few people seem to have heard of them. Here’s another charity who need us as much as we need it.