A team of archaeologists is racing against time to uncover Nova Scotia’s coastal Mi’kmaq history before it is washed away forever.

This project is part of COASTAL (Community Observation, Assessment and Salvage of Threatened Archaeological Legacy), led by Matt Betts, curator of Atlantic provinces archaeology at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que.

Working with Betts are Katherine Patton, a lecturer in the University of Toronto’s department of anthropology, and Gabe Hrynick, an associate professor in the University of New Brunswick’s department of anthropology.

Betts and his team started work on Aug. 9, investigating and documenting shell midden sites located along Nova Scotia’s southwestern shore. They want to complete this work before these sites are washed away by coastal erosion. The archaeologists will be in Nova Scotia until Sept. 4.

Besides the sites near Sable River in Shelburne County, they also visited Freeport in Long Island (Digby County), and they’re hoping to go to Seal Island (Argyle County) and Outer Bald Tusket Island (off the coast of Yarmouth County).

Betts also led the Canadian Museum of History’s E’se’get Archaeology Project focusing on Mi’kmaq shell middens in Port Joli (Queens County). Port Joli boasts the densest concentrations of shell middens in Nova Scotia. The E’se’get Archaeology Project will culminate in the publication of a book this September.

E’se’get is a Mi’kmaq word which means “to dig for clams.” Shell middens are ancient refuse heaps into which people discarded food waste, in this case the inedible portions of clams.

Because Nova Scotia soils are so acidic, preservation of bone, wood and other organic materials buried in it is rare. But shell middens change the soil. As the shells degrade, calcium carbonate leaches out into the surrounding acidic soil, neutralizing it and preserving anything else contained in the soil.

In 2008 and 2009, Betts and his team conducted walking surveys along the entire coastline of the west side of Port Joli and into Port L’Hebert. After finding at least 21 shell middens located along Port Joli Harbour, Betts’ team surveyed 19 of them. Fieldwork wrapped up in 2012, followed by five years of organizing, interpreting and analyzing the over 22,000 artifacts found.

During this project, one of the things Betts came to realize is the serious threat coastal erosion poses to archaeological sites along the South Shore. As a result, he and his team returned in 2017 to conduct a baseline assessment of the impact of coastal erosion.

What the archaeologists found was alarming. They visited 21 coastal sites on the South Shore. Of the 17 sites known of before 2000, 93 per cent have been effectively destroyed. As Betts said at the time, “To date, we've only found a handful of artifacts from the sites we've visited; there is simply nothing left to salvage from these impacted sites. Their history is lost forever.”

During that 2017 visit, the team also held a public event at the Harrison Lewis Coastal Discovery Centre in East Port L’Hebert. Around 40 people attended that session, bringing artifacts and sharing their knowledge of at least six endangered sites Betts was not previously aware of.

The team returned this year in hopes of finding intact archaeological deposits at these sites.

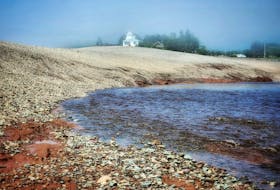

On Aug. 11, they hiked out to an archaeological site containing evidence of a shell midden adjacent to Craig’s Island, near Sable River. At low tide, a deposit of broken clam shells lining the bank suggested that this had once been a Mi’kmaq house, or at least a clam-harvesting site. They also found quartz flakes, which indicated that tool making had been done here.

Those initial findings don’t tell them much, Betts explains.

“People were definitely making stone tools very close by. They were probably living here, too. They certainly were harvesting a lot (of clams) here. But it’s just very difficult for us to know what they were doing here, because there’s no context left behind.

“That’s the sad part of it. Essentially we know they were here, they were eating clams and they were making stone tools, but that doesn’t really tell us the history of the place.”

The team measured the perimeter of the site and did a soil probe, in which they found charcoal. The charcoal will need to undergo radiocarbon dating to determine its age.

After examining the Sable River site, they came to a discouraging realization. It has been nearly destroyed by coastal erosion. The line of clam shells along the bank actually represents the back end of what was originally there. The bank has been continually undercut by waves washing in, then fanning the material out along what is now the shoreline.

But all was not lost. As the team got ready to leave, Patton’s “spidey sense” was tingling, and she suggested returning to a portion of the site farther up above the bank, covered by thorny vegetation. The team had already examined that area earlier in the afternoon, finding the same kind of surface shell they found along the shore.

Patton began digging and, to her delight, found an intact shell midden.

“That changes the priority of this site dramatically,” Betts notes. “It is a near-destroyed site, but it makes it a higher priority because of the intact deposit.”

The team plans to return to the Sable River site to see if they can find any artifacts that might have been preserved in that shell midden.